Photo by Michelle Underwood

Summer has arrived in Chicagoland. Finals week at Trinity was the last week of April and Commencement was May 2. May 15 was the last day for faculty members on nine-month contracts. As June approaches, I’m in fewer meetings. I’ve begun thinking about the two history courses I will be teaching in the fall: History 204, the first half of the American History survey, and History 401, the Senior Seminar.

I enjoyed two book events in April. The first was an online Iowa History 101 event sponsored by the State Historical Society of Iowa (SHSI) on April 10 at noon. The zoom session was attended by about a dozen people. My talk addressed what we know about Laura’s faith and about Laura and Rose’s contributions to the Little House books, particularly as they address Christianity and the church. I also discussed the Ingalls’s family’s one-year stay in Burr Oak, Iowa, in 1876 and 1877. There were some great questions at the end. The session was recorded and a link is at the end of this post.

Then I was able to travel to the Missouri Cherry Blossom Festival in Marshfield, Missouri. I was there on Friday, April 25 and Saturday, April 26. The mornings and early afternoons of both days I was able to sell and sign books (I took copies of both A Prairie Faith and my second book, Almost Pioneers) in Marshfield’s Community Center, along with a number of movie and television stars from the mid to late twentieth century. Nine actors were there from “Little House on the Prairie,” including Dean Butler, who played Almanzo, and Alison Arngrim, who played Nellie Oleson. There were also three actors from “The Waltons,” and others from “Leave it to Beaver,” “Dallas,” “Barney Miller,” It’s a Wonderful Life, and a variety of other shows and movies. Michelle Underwood, a southwest Missouri author who also works at the Laura Ingalls Wilder Home in Mansfield, had a table next to mine. She has written a book giving a “behind the scenes” look at the Wilder Home. We enjoyed talking while we worked to attract the crowds who waited in line to get autographs from the “Little House on the Prairie” stars. I ultimately sold about twenty books.

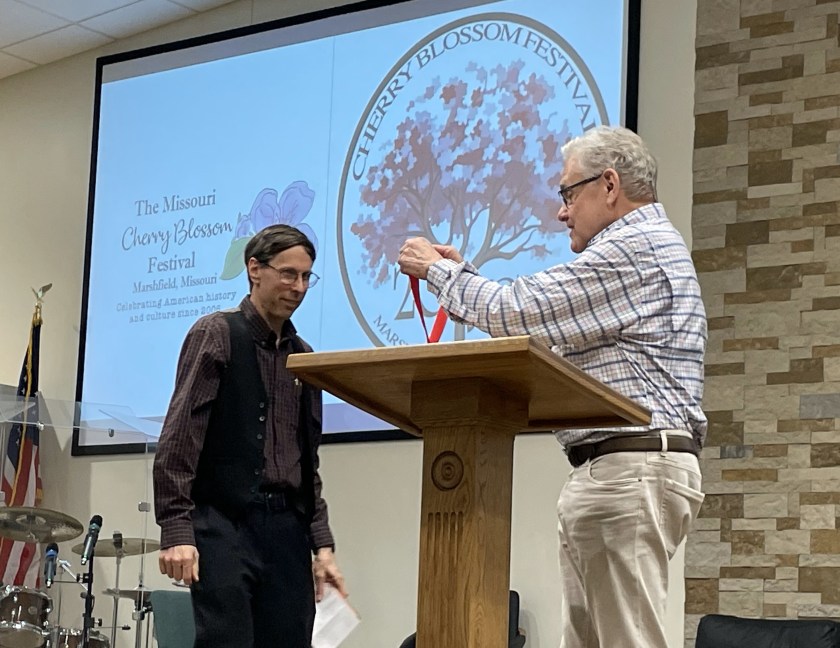

On Friday afternoon I went to the Marshfield Assembly of God church to receive the Ella Dickey Literacy Award. Bill Anderson presented me with the award. The other awardees were the Rev. John Marshall, a retired Baptist Pastor who has written a book on the faith of Abraham Lincoln, and Paul Landis, a Secret Service Agent for John F. Kennedy who has written a memoir about his experiences. I was honored to receive the award, which is named after a beloved, long-time librarian in Marshfield.

John Marshall, me, and Paul Landis. Photo by Sarah Manley

Later Friday afternoon, I attended the Dred Scott Reconcilation Forum, hosted by Lynne Jackson, a descendant of Dred and Harriet Scott. She interviewed Dr. Bryan Moore, the pastor of Jubilee Community Church in north St. Louis and a distant relative of Nat Turner. I also got to judge a cherry pie contest. On Saturday morning, I attended Rev. Marshall’s session about Lincoln; his comments were very insightful. It was great to catch up with Bill Anderson and Sarah Manley. Many thanks to Sarah for taking the pictures during the ceremony. Many thanks also to Rev. Nicholas Inman, Director of the Laura Ingalls Wilder Home in Mansfield and the driving force behind the Festival, for his gracious invitation.

Now I’m just waiting to hear the announcement of the Book of the Year for Biography from the website Foreword. A Prairie Faith is one of eight finalists. Lord-willing that will be announced in June.

If you’re interested in having me speak, please let me know (john.fry@trnty.edu). Thanks for reading!

Links:

STL listing of events at Missouri Cherry Blossom Festival

My second book: Almost Pioneers: One Couple’s Homesteading Adventure in the West

Michelle’s Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Rocky Ridge Farm: A Detailed Look Behind the Scenes

Paul Landis’s The Final Witness: A Kennedy Secret Service Agent Breaks His Silence After 60 Years

John Marshall’s Lincoln and Christianity: Essays on Lincoln’s Religious Life

The Laura Ingalls Wilder Home and Museum in Mansfield

Foreword Book of the Year Finalist Announcement

List of Foreword Book of the Year (INDIES) Finalists for Biography

Foreword’s Listing for my book

Bill Anderson presenting me with the Ella Dickey Literacy Award. Photo by Sarah Manley