Again it has been months since I posted to this blog. My apologies to followers.

Quick update on my book: I completed an ugly draft of chapter 8 this last summer, and my research trip to Missouri and Kansas meant I was able to fill in missing pieces of chapters 2, 6, and 7. That means that I have now completed drafts of chapters 1 through 8, so I will need to write chapters 9, 10, and 11 and edit the whole when I am on sabbatical next spring. I have some hopes of accomplishing this. This fall, much of my time has been taken up with teaching a new upper-level history course at Trinity and my administrative duties.

During the last few weeks, however, I have had the opportunity to read the second volume of Brooks Blevins’s A History of the Ozarks: The Conflicted Ozarks. Based on the most recent historical research, the book was mind expanding for my understanding of the region. It is a densely-written book with an incredible amount of detail. The overall contours of the history have expanded my understanding of Wright County, Missouri, where Laura and Almanzo Wilder settled in 1894.

Blevins begins by describing the population of the Ozark Uplift, from eastern Oklahoma to northwestern Arkansas and southern Missouri. The whites of the region were a mixture of westerners, midwesterners, and southerners. The region had fewer slaves per capita than the south, though the existence of slavery colored life everywhere and for everyone. The central chapters of the book describes how society in the Ozark Mountains were destroyed by the Civil War. During the first two years of the war, both Union and Confederate armies marched across the region, living off the land by confiscating foodstuffs and livestock and fighting several major battles. Once the regular armies had moved on, state militias, irregular military units, and what we might call gangs today ranged through the region, attacking opponents, destroying property, and at times displacing entire populations. After the war ended, Reconstruction took different forms in Arkansas, which was occupied by the U. S. army, and Missouri, which was not. In both areas, however, freed slaves worked to find ways to support their families and former slaveowners found new ways of organizing their farms. Bloodshed continued across the region during reconstruction, involving the Ku Klux Klan in Arkansas and vigilantes known as Bald Knobbers in parts of southwestern Missouri. Open violence had largely ended by the middle of the 1870s, but spectacular reports of Bald Knobber lynchings and reprisals were reported in newspapers until 1888.

The last chapter of the book is titled “Reconstructing Society and the Economy in the Ozarks.” It describes how the building of railroads, the development of mining and timbering, and the founding of public schools and educational institutions connected many towns and families to the rest of the country, both economically and culturally. However, areas bypassed by the railroads and further from natural resources remained less prosperous and less “civilized.” In an Epilogue, Blevins argues that these areas and the vigilante action that occurred there became fascinating to Americans in urban areas during the late nineteenth century. Ultimately, the residents of this other world were immortalized by Harold Bell Wright’s The Shepherd of the Hills, published in 1907. The cultural term “Ozarks,” not referring to the town of Ozark or to the Ozark Mountains, appeared in print for the first time in the New York Times in 1887. The term became used for the “backward” portions of the region, much as the term “Appalachia” was used during the same period. These characterizations flattened out the more complex realities of the region for decades to come. In the third volume of the history, which is set to be released in November, Blevins promises to provide a more complex portrait of the region’s past and present.

Reading this book was mind-expanding for me. I did not realize how brutal the Civil War was in Missouri and Northern Arkansas, despite my appreciation of the movie Ride With the Devil (1999) which is set in Missouri during the war. I also learned several things that will be useful for my work on Laura Ingalls Wilder:

- Wright County and Mansfield, Missouri, are in the Central Plateau of the Ozark uplift. (p. 8)

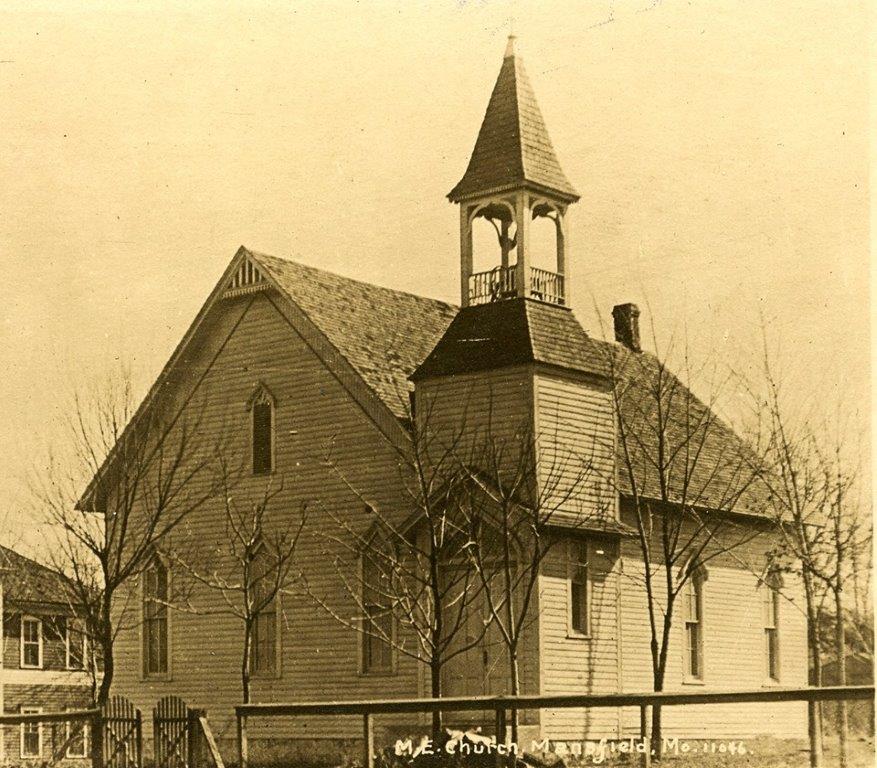

- The first railroad that went through Mansfield was the Kansas City, Fort Scott and Memphis, sometimes known as the KC, FC & M. It built east from Springfield to Willow Springs in 1881 and 1882. (196)

- Railroads made money from selling land along their routes, and they relied on population to use their services. In areas where there was lead, zinc, iron, or large stands of trees, mining and timber paid the freight. This was not the case in the central plateau, so “the KC, FS & M eventually turned to promotion to generate profitable shipping, dubbing the country between Springfield and Thayer the ‘Land of the Big Red Apple’…” (196) This slogan will probably be familiar to Wilder readers familiar with the advertising that brought Almanzo and Laura to Mansfield in 1894. The KC, FS & M was bought out by the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad in 1901.

- Laura and Almanzo lived in an area served by a railroad line and therefore more prosperous than many areas, some of them not far from the town of Mansfield. Blevins concludes: “The result of these factors in the decades after the war and Reconstruction was the gradual development of a divergent society in the Ozarks, one of haves and have-nots. While the farms and towns of the Springfield Plain and the river valleys and the rail lines prospered in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, those in other less-advantageous areas stagnated or declined…” (235)

Blevins’s interest is almost completely in the direction of military, economic, and social history. Churches are mentioned only a few times in the book: as a key feature of community for slaves (23-24), when the U. S. War Department allowed Northern Denominations of Christian churches to seize the property of Southern Congregations during the War (148), and when figures were connected with particular churches.

Still, the book is expansive, detailed, and will reward the careful reader. I believe that the observations I outlined above will enrich my chapters about the Wilders’ time in Mansfield, including providing important context for their farm operations, Almanzo’s work in town (which was mostly related to the railroad), and Laura’s work with the Mansfield Farm Loan Association.

Thanks for reading.

Links:

Trinity Christian College – https://www.trnty.edu/

Brooks Blevins, A History of the Ozarks:

Volume 1, The Old Ozarks

Volume 2, The Conflicted Ozarks

Volume 3, The Ozarkers

My presentation was on Friday morning. I was followed by an excellent talk by Kipton and Ethan Smilie about the ways that the Little House books show the formation of social capital in their depictions of late nineteenth century education, and by a fascinating demonstration by Rich Kurz about how he created a scale three-dimensional model of the Ingalls store in DeSmet, South Dakota, from extant pictures.

My presentation was on Friday morning. I was followed by an excellent talk by Kipton and Ethan Smilie about the ways that the Little House books show the formation of social capital in their depictions of late nineteenth century education, and by a fascinating demonstration by Rich Kurz about how he created a scale three-dimensional model of the Ingalls store in DeSmet, South Dakota, from extant pictures. I left a little early on Friday morning so that I could stop in Mansfield to see the Historic Home and Museum on my way home. I was able to tour both the farmhouse that Laura and Almanzo built between 1894 and the 1910s and the “rock house” that was built by their daughter Rose Wilder Lane for them during the late 1920s. Laura wrote Pioneer Girl and the first several Little House books while living in the rock house between 1828 and 1936. Both of the houses are amazingly well built and well kept. They are also quite small. I guess that’s appropriate for someone famous for writing about Little Houses. I had forgotten that Laura was only four feet, eleven inches tall. Since Wilder was famous when she died in 1957, the farmhouse immediately became a historic home, and almost everything inside it belonged to her and Almanzo. The rock house had been sold and was not reacquired until the late 1900s, but it has been restored. I was hoping to walk the path between the two houses that was used by Wilder and Lane to see each other when they were writing. Unfortunately, I was told that it was flooded.

I left a little early on Friday morning so that I could stop in Mansfield to see the Historic Home and Museum on my way home. I was able to tour both the farmhouse that Laura and Almanzo built between 1894 and the 1910s and the “rock house” that was built by their daughter Rose Wilder Lane for them during the late 1920s. Laura wrote Pioneer Girl and the first several Little House books while living in the rock house between 1828 and 1936. Both of the houses are amazingly well built and well kept. They are also quite small. I guess that’s appropriate for someone famous for writing about Little Houses. I had forgotten that Laura was only four feet, eleven inches tall. Since Wilder was famous when she died in 1957, the farmhouse immediately became a historic home, and almost everything inside it belonged to her and Almanzo. The rock house had been sold and was not reacquired until the late 1900s, but it has been restored. I was hoping to walk the path between the two houses that was used by Wilder and Lane to see each other when they were writing. Unfortunately, I was told that it was flooded. I also looked through the new Museum at the site, which was just finished last year. There is an 8-minute orientation film and a lot of artifacts from Laura and Almanzo’s lives on display. Several are related to my work on Wilder’s faith:

I also looked through the new Museum at the site, which was just finished last year. There is an 8-minute orientation film and a lot of artifacts from Laura and Almanzo’s lives on display. Several are related to my work on Wilder’s faith: