When I did my research trip to Missouri two weeks ago, I took a day to drive to Independence, Kansas, and the Little House on the Prairie Museum. This was the last of the places that Laura Ingalls Wilder had lived in the Midwest that I wanted to visit while writing my book.

After spending a day and a half in the State Historical Society of Missouri office in Rolla (discussed in my post last week), I drove to Joplin, Missouri, and stayed overnight, and then finished the trip to Independence the next morning. I was surprised by how quickly I left the rolling hills of the Ozark mountains and entered the flat plains of southeastern Kansas, and it occurred almost at the moment when I drove out of Missouri. It was nice to be off interstate highways, although I did have to pay attention to the road to dodge small turtles who occasionally were slowly making their way across my lane. I drove through the town of Independence and arrived at the Little House on the Prairie Museum in the middle of the morning.

I was welcomed by the donkeys in the pasture next to the barn (it was striking how loud they were) and then by Rhonda Stephen in the Welcome Center / Gift Shop. This property was where the Ingalls family lived in 1869 and 1870, when Laura was 2-3 years old. It was also where Laura’s younger sister Carrie was born. The site was immortalized in the third Little House book, Little House on the Prairie. Unfortunately, unlike De Smet, South Dakota, and Mansfield, Missouri, this site does not have an actual house where Laura lived; the log cabin here was just a replica. The Museum has also moved a historic Post Office from Wayside, Kansas, and a one-room schoolhouse from Sunnyside, Kansas, to the property; both are from the late 1800s. The farmhouse on the property, now used as the gift shop, was built in the late 1880s as well. But none of these structures has a direct connection to the Ingalls family.

There is, however, a hand dug well on the property, which was probably dug by Charles Ingalls and one of his neighbors. The existence of this well helped researchers during the 1960s decide that this was where the Ingalls family lived, since the first legal land filings were in 1871, after the Ingalls had left the area to move back to Wisconsin. I sat a bit in the back yard to look at the hand dug well with rocks around it. I thought I should stay a while, since it had taken a long time to get here. A long time in several different senses: First, the site is over 650 miles from my home, and I had done the trip by driving six hours to Rolla, then three hours to Joplin, then two hours to the site. Second, I had been planning to visit this site since I began my work on Laura Ingalls Wilder’s faith in 2016. Third, I’ve actually been reading and thinking about Laura since 1995. Finally, it must have taken the Ingalls family an incredibly long time to travel to this place. Google maps says that it is almost 650 miles from Pepin, Wisconsin.

The well has been filled with concrete, so one can’t look down into it. But one can imagine. The space surrounding the homestead is no longer that empty; U. S. Route 75 is visible in the distance, and there are other roads and trees in most directions. The land behind the property has folds and gullies; there are flat fields in front. Obviously, much has changed in the 150 years since the Ingalls family moved away. It was good to be there, looking at something that Charles Ingalls had made, and thinking about the passage of time.

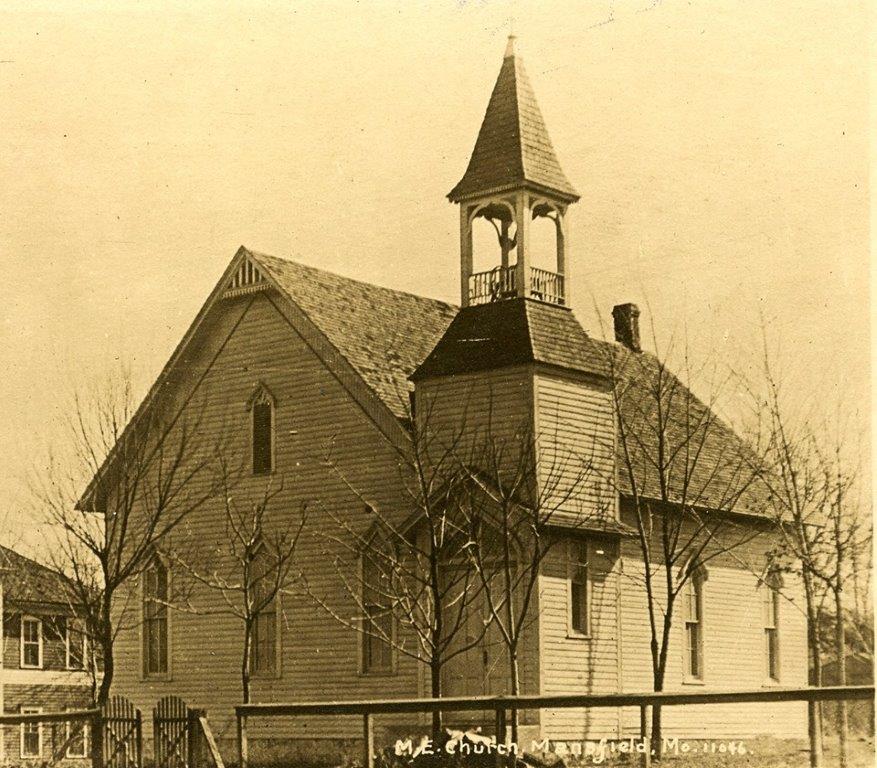

In the hour I had been there, several older couples and one family with young children had arrived. So after a second brief conversation with Rhonda, I headed back to Independence. I wanted to find out if there were churches in the area when the Wilders were living there. So I went to the Independence Historical Museum. Sylvia Augustine is the Coordinator there, and she brought out a Montgomery County History published in 1995 that had information about the first churches founded in Independence. It turns out that Roman Catholic missionaries had reached out to the Osage in previous decades, and they established a mission station in Independence in 1869. Father John Schoenmakers was taking the sacraments to Catholic settlers that year and the next. A group of Methodists also began meeting for worship in Independence several times a month in 1869. As the white population of both Independence and the land around it increased, more churches were planted; by the time the Ingalls left the area, there were Baptist and Presbyterian congregations meeting in Independence. It does not appear that the Ingalls had any contact with these groups. I was grateful for Sylvia’s assistance.

On my way out of town, I pulled off U. S. Route 160 to a county road with an incredibly scenic bridge over the Verdigris River. I took some pictures of the river, and some of the bridge. I then continued east between fields of pastureland and corn, back towards Missouri. I had appointments at the Laura Ingalls Wilder Historic Home and Museum in Mansfield the next morning, which I will describe in my next post.

Thanks again to my institution, Trinity Christian College, for funding my travel. Thanks to all of you for reading.

Links:

My post about research in Rolla last week

Little House on the Prairie Museum