In the gift shop at the Laura Ingalls Wilder Home and Museum, Mansfield

Last week I was able to travel to Missouri for several engagements. On Wednesday, September 25, I from Chicagoland to Branson and stayed overnight there. The next day I drove to the College of the Ozarks (they call it the C of O), which is just south of Branson. There, Dr. Aleshia O’Neal gave me a wonderful tour of the campus before I spoke in her class. Dr. O’Neal is an English Professor at the C of O who grew up on a farm in Missouri. So we enjoyed looking at all the tractors and barbed wire in the college’s tractor museum. We also went to Patriot’s Park, Williams Memorial Chapel, and the scripture garden that overlooks the White River. The C of O is a work college, meaning there is no tuition, but all students work fifteen hours a week on campus or in the local community. I did not realize how many different on-campus business operations this would require. We visited the stained glass studio and grist mill, and I saw the greenhouses and barns for the cows. We finished at the Ralph Foster Museum, which has artifacts from all periods of Ozarks history. I then spoke about my research on Mrs. Wilder in English 3023, the American Novel, to eight students and several faculty members. The English Department treated me to lunch at the C of O’s Keeter Center, which features an excellent restaurant, as well as a hotel and conference center. Many thanks to Dr. O’Neal and to Dr. Ethan Smilie, Humanities Division Chair, for their invitation and hospitality. I met Dr. Smilie at LauraPalooza in 2017, and we’ve corresponded ever since.

Me with Dr. Ethan Smilie and Dr. Aleshia O’Neal

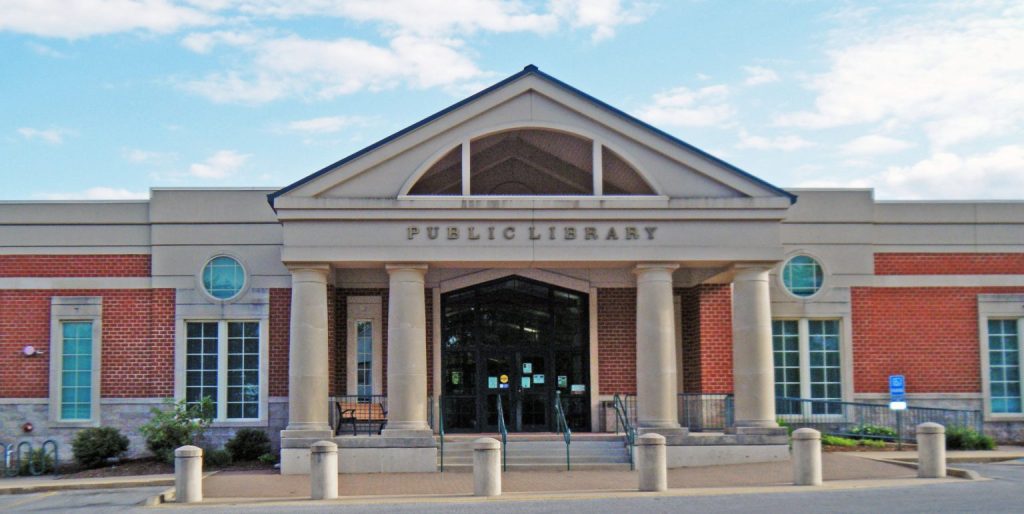

That afternoon I drove from the Keeter Center to West Plains, a town of about 12,000 people in south-central Missouri. I spoke at the West Plains Public Library at 5:00. There were about thirty people there, including a woman who was originally born in the south suburbs of Chicago. There were also several families from Covenant Reformed Church, which is a congregation in my Presbytery. That night I stayed with a family from that church and really enjoyed my time with them and their daughter and three sons. They reminded me of my family about 20 years ago. Many thanks to Greg Carter and Dianna Locke for hosting me at the Library, and to the Nortons for their hospitality.

West Plains Public Library

On Friday, September 27, I drove from West Plains to Mansfield for the 49th Annual Wilder Days celebration. I went by way of Ava, which is a town that Laura and Almanzo Wilder often visited on Sunday afternoons, but which I had never been to. This got me off the four-lane highway, which meant I saw some really beautiful views of the Ozarks. Certain areas really reminded me of Western Pennsylvania, where I grew up. Once I got to Mansfield, I went to the Laura Ingalls Wilder Home and Museum outside of town and reacquainted myself with the site. I walked through the farmhouse, over the path to the rock house, and through the rock house—tours were self-guided because of Wilder Days. I also went through the museum and saw that my book was for sale in the middle of a bookcase of works about Mrs. Wilder. There now is also a recreation of Almanzo’s garage, just opened this year. I also visited the Mansfield Area Historical Museum in downtown Mansfield. It is housed in a replica train station and has a variety of artifacts from local history, including materials about Carl Mays, who played major league baseball fifteen years for the Red Sox, Yankees, and Reds. I also got to see the Mansfield public school fourth graders sing in the square. They did great.

Friday evening, I went to the Fifth Annual Wilder Dinner, a fundraising event for the Laura Ingalls Wilder Home and Museum. It was held at the Mansfield High School. Before the prayer, a local musician played two songs on Pa’s Fiddle, the violin that belonged to Charles Ingalls. It gave me chills to hear the instrument that Laura wrote so much about. After dinner, there was a live auction of a variety of pieces of Wilder memorabilia. Dean Butler also spoke; he played Almanzo in the TV series “Little House on the Prairie” from 1979 to 1983. I had previously heard him speak at LauraPalooza in 2022. Friday night, I was able to stay at a house owned by the Wilder Home.

David Wilson playing Pa’s Fiddle

Saturday morning, I was able to hear Pa’s Fiddle again, this time for forty-five minutes, in front of the Wilder Home. I then signed books in the entryway to the museum from 10 am to noon. Dean Butler was signing copies of his new book, Prairie Man in the back of the museum. The line for him wound through the museum, out the front door, down the steps, and along the parking lot. At lunch, I went downtown and bought a pie from the Historical Museum’s fundraiser and a bag of kettle corn. I also got to see the Mansfield Wilder Days Parade. I then went back to the museum and signed books from 2 to 4 pm. I then drove back to Chicagoland. Many thanks to Rev. Nicholas Inman, Director of the Wilder Home and Museum, and to staff members Susie, Vicki, Marie, Tana, Clinton, and everyone else who made my visit there excellent.

Up next for me is a book celebration at Trinity next Wednesday afternoon. There are four faculty members who have published books in the last twelve months. I will also be signing books at the Barnes & Noble in Orland Park, Illinois on Saturday, October 19 from 1 to 3 pm. Anyone in Chicagoland is invited to attend! (Put in link)

Thanks again for your support!

Links:

Laura Ingalls Wilder Historic Home and Museum

Mansfield Area Historical Society and Museum

Book Signing at Barnes & Noble Orland Park, Illinois