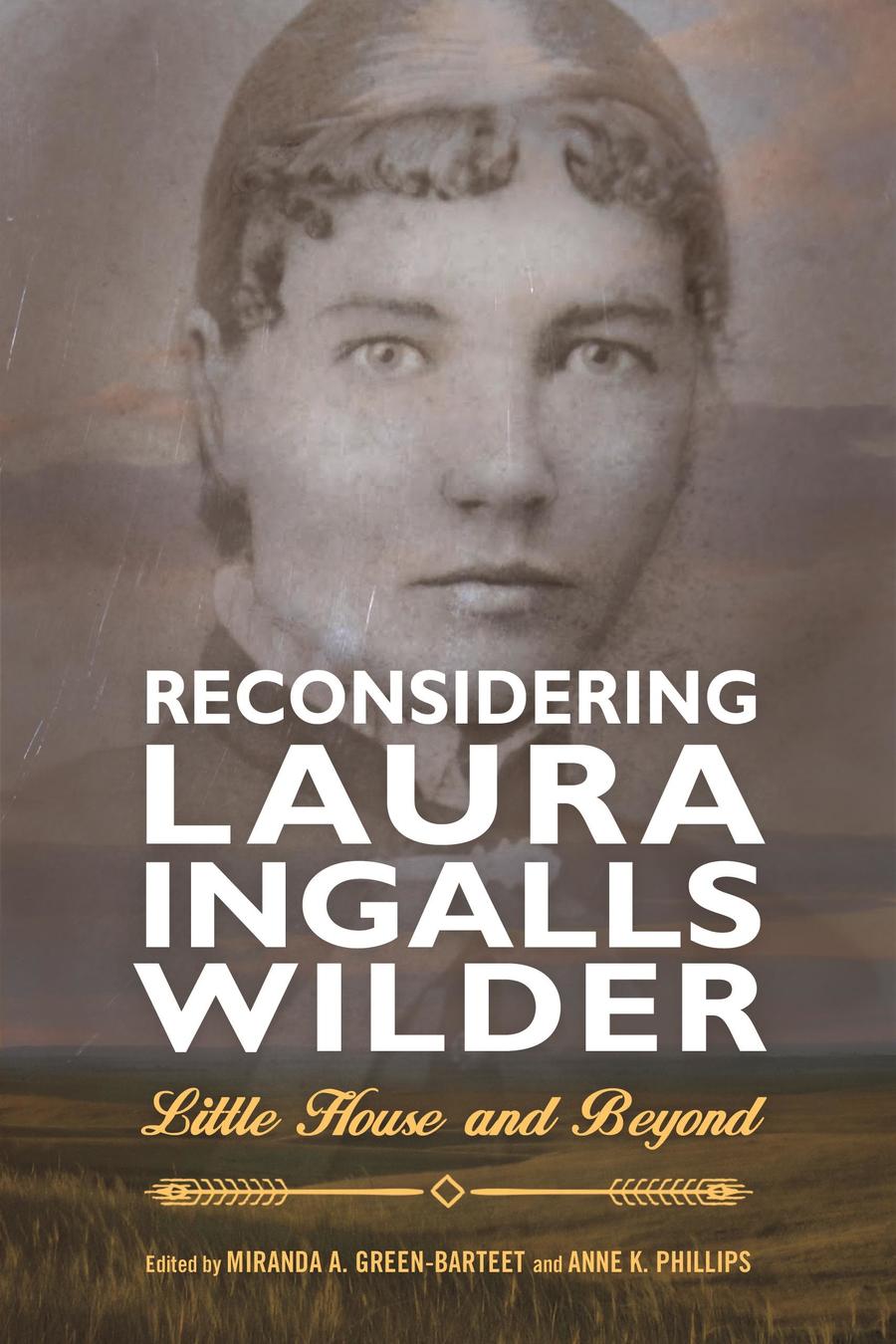

When I sat down to write this entry, I was shocked to realize that it has been five months since I have contributed anything to The Faith of Laura Ingalls Wilder. Actually, I wasn’t shocked. I knew that it has been a long time. But I have tried to keep doing some reading about Laura Ingalls Wilder. During this semester, that has meant reading a couple of essays in Reconsidering Laura Ingalls Wilder: Little House and Beyond each week. I finished the book yesterday.

Published by the University of Mississippi Press earlier this year, Reconsidering Laura Ingalls Wilder contains fifteen essays by scholars, and it presents some of the most recent academic scholarship on Wilder and the Little House books. Most of the authors are literature scholars; several have degrees in creative writing, American studies, women’s studies, and gender studies. There are no historians. Like most books of essays, I found some of the pieces to be stronger than others. Five stood out to me as providing particularly helpful examinations of Wilder’s writing:

- Keri Holt and Christine Cooper-Rompato, “The Complicated Politics of Disability: Reading the Little House Books and Helen Keller.” The authors examine the Little House books’ depiction of Mary’s blindness, which is central to the later novels. They point out that the ways that the books depict Mary’s contributions to family life show her “individualism, self-sufficiency, and independence,” (35) which was a contrast to most other children’s books’ depictions of people with disabilities. These traits were also stressed by Helen Keller in her writing during the early twentieth century. Ironically, however, both Wilder and Keller stressed independence and distanced themselves from outside support; the Little House books do not mention that Dakota Territory paid for Mary’s tuition at the Iowa School for the Blind, and Keller often publicly refused monetary gifts and quietly accepted them later. I greatly appreciated Holt and Cooper-Rompato’s nuanced description of the complicated nature of these individuals’ lives and works.

- Vera R. Foley, “Naked Horses on the Prairie: Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Imagined Anglo-Indian Womanhood.” This essay provided a close reading of Laura’s interactions with horses in the Little House books and The First Four Years. Foley describes Laura as “a young girl caught between the influence of a genteel mother and an unstable frontier.” (51) The result, Foley argues, was that Laura embraced an outdoor, active femininity, not Ma’s domesticity. (49-50) A key part of how the books describe this process involves horses: from the Indians riding away on ponies at the end of Little House on the Prairie, to her racing with Lena across the plains in By The Shores of Silver Lake, to her courtship which is conducted almost exclusively on buggy and sleigh rides, to her riding of Trixy in the First Four Years. Fascinating.

- Jenna Brack, “Her Own Baby: Dolls and Family in ‘Indians Ride Away.’” This essay presents the most multidimensional explanation of Laura’s shocking demand for a Native American baby at the end of Little House on the Prairie that I have read. You may not agree with her interpretation; I don’t agree with it completely. Unfortunately, it is impossible to describe in a short space.

- Jericho Williams, “Breathing Literary Lives from the Prairie: Laura Ingalls Wilder and the Promises of Rural Women’s Education in the Little House Series.” This essay compares the description of Laura’s career as a teacher to depictions of teachers in Hamlin Garland’s Rose of Dutcher’s Coolly and Willa Cather’s The Song of the Lark. While the female protagonists in Garland and Cather’s books leave their small towns for success in urban areas, Wilder’s works reject the idea that “rural women lead inferior lives.” (134) Williams continues: “In Wilder’s view, rather than just a means for talented women to leave their hometowns, education is a multifaceted process that consists of learning rural arts and skills, living within one’s means, adapting to one’s environment, and assisting one’s family members and community.” (134) I think that this is an insightful statement about key aspects of Laura’s overall worldview, not just her view of education.

- Christiane E. Farnan, “The Undergraduate American Studies Classroom: Teaching American Myths and Memories with Laura Ingalls Wilder.” Farnan has her college students read Little House in the Big Woods, Farmer Boy, and Little House on the Prairie in conversation with other classic books about farming and the frontier by Mary Rowlandson, Thomas Jefferson, Hector St. John Crevecoeur, Horace Greeley, Frederick Jackson Turner, James Agee and Walker Evans, and Henry Nash Smith. The essay asserts that her current students easily understand Big Woods and Farmer Boy as depictions of the agrarian ideal, but they often interpret Little House on the Prairie as a critique of Native American removal and agrarian occupation. Pa uproots his family, takes them into danger in many forms (the frozen lake, the high river, fire, wolves, hostile Native Americans), then abandons all of their work because of a rumor. Nobody is better off at the end of the book. It was a reading that I hadn’t thought about before, and not one that I especially share, but I can see how her students come to it.

Unfortunately for my particular project, most of the authors ignore religion and faith. The one significant consideration is in Anna Thompson Hajdik’s “The Wilder Mystique: Antimodernism, Tourism, and Authenticity in Laura Ingalls Wilder Country,” a review of the development of some of the Wilder historic homesites and an examination of some of the sources of their appeal during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Hajdik notes the importance of the books to Christian homeschooling families and the Amish. The homeschooling connection has been mentioned by other authors (and I have numerous personal examples), but this is the first time I’ve read about the Amish. The citation for this observation was a personal conversation from 2006.

Reconsidering Laura Ingalls Wilder provides a number of fresh looks at the Little House books. I was pleasantly surprised that the authors are willing to consider the works on their own terms, not just condemn them for not living up to how people today would deal with the subject matter. It does not provide any new biographical or historical information about Wilder, but it does provide some new and interesting ways to approach Wilder’s work.

As always, thanks much for reading.

(All citations are from: Reconsidering Laura Ingalls Wilder: Little House and Beyond. Edited by Miranda A. Green-Barteet and Anne K. Phillips. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2019.)

Publisher’s site and picture credit: https://www.upress.state.ms.us/Books/R/Reconsidering-Laura-Ingalls-Wilder